“The Best School for a Writer”: Madeleine and Miss LeG

When my teacher announced the end of the silent reading period, I crawled out from behind the armchair in the corner of my second-grade classroom. I’d hidden there to maximize my peace and quiet. I blinked at the influx of light, feeling as though I were returning from another planet. And in a way, I was: I’d been on Camazotz with the Murrys, absorbed in A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L’Engle.

Two years later, my classmates and I were assigned the task of writing a letter to an author we admired. Having been told that I could not write to C.S. Lewis about Narnia because that author was deceased, I addressed my letter to L’Engle. By that point, I’d devoured the rest of the Time Quintet books, captivated by their fantastical plots and the relatability of heroine Meg Murry, who was bookish, bespectacled, and impatient, just like me. L’Engle replied with a form letter that included a handwritten note at the bottom: “Thanks for the photo!” I don’t recall what I wrote or what photo I sent, but I remember taking great satisfaction in knowing that this world-famous novelist had read my letter.

Madeleine and Marie Donnet, ca. 1941

I didn’t know then that Madeleine L’Engle had decades of experience answering fan mail, though not initially her own. In 1940, while a student at Smith College, Madeleine and her best friend Marie Donnet wrote to the illustrious actress, director, and producer Eva Le Gallienne, asking her to consider directing one of Madeleine’s plays. In reply, Miss LeG (pronounced “le-GEE,” as everyone called her) encouraged them to look her up when they moved to New York after graduation. Two years later, a series of fortunate events led the two young women to visit Miss LeG at her apartment, where Madeleine happened to mention that she could type. (See Becoming Madeleine for the full story.) Hired on the spot to help answer Miss LeG’s correspondence, Madeleine went on to work with her for more than two years—not only as a typist, but also as an actress, understudy, and assistant stage manager.

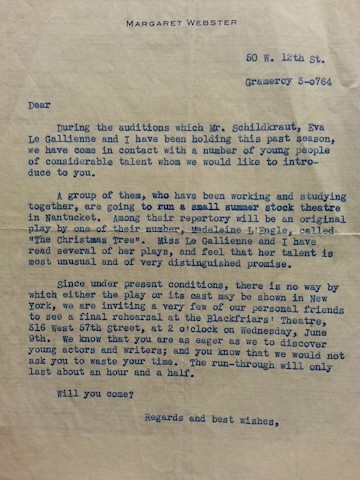

I first learned of Madeleine’s connection with Miss LeG in Helen Sheehy’s vividly rendered biography, Eva Le Gallienne, which I read shortly after graduating from college in 2007. “She loved me in a benign, maternal way,” Madeleine told Sheehy. “She was incredibly kind and encouraging to me as a writer.” Indeed, Miss LeG championed Madeleine’s writing from the start, as did her  then partner, the director Margaret Webster. In 1943, Webster invited a group of theatre professionals to a reading of Madeleine’s play The Christmas Tree, writing, “Miss LeGallienne and I have read several of her plays, and feel that her talent is most unusual and of very distinguished promise.” Madeleine fulfilled that promise in 1944 when she penned her first novel, The Small Rain, inspired by her theatrical adventures with Miss LeG and written in the wings of the touring production of “Uncle Harry.” Though she soon transitioned fully from playwriting to novel writing, Madeleine would later assert that the theatre was “the best school for a writer,” and the time she spent in Miss LeG’s inner circle would remain a treasured memory.

then partner, the director Margaret Webster. In 1943, Webster invited a group of theatre professionals to a reading of Madeleine’s play The Christmas Tree, writing, “Miss LeGallienne and I have read several of her plays, and feel that her talent is most unusual and of very distinguished promise.” Madeleine fulfilled that promise in 1944 when she penned her first novel, The Small Rain, inspired by her theatrical adventures with Miss LeG and written in the wings of the touring production of “Uncle Harry.” Though she soon transitioned fully from playwriting to novel writing, Madeleine would later assert that the theatre was “the best school for a writer,” and the time she spent in Miss LeG’s inner circle would remain a treasured memory.

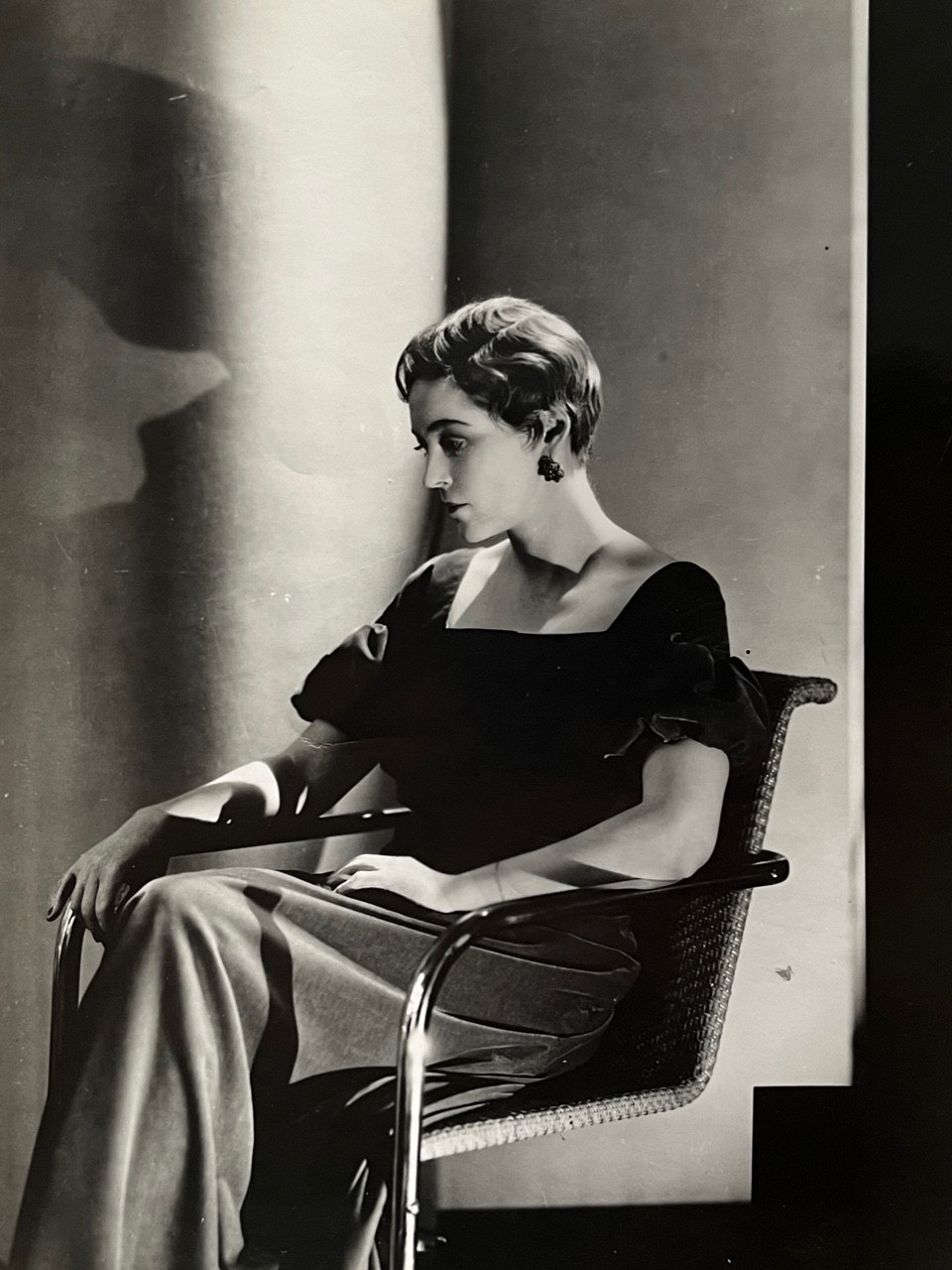

Eva LeGallienne

By the time she met Madeleine L’Engle, Eva Le Gallienne was one of the most accomplished theatre artists in America. Born in London and raised in Paris and Copenhagen, LeGallienne—who liked to say she was “a step ahead of the century,” having been born in 1899—became an overnight success in the West End at age sixteen, then moved to New York to pursue broader theatrical horizons. She achieved Broadway stardom at twenty-one and national celebrity status at twenty-four, but renown was not her ambition: she wanted to grow as an actress, and she felt that in order to do so, she couldn’t keep playing in long-running shows. The repertory system, in which a single acting company performed a variety of plays in constant rotation, didn’t exist in America, where all theatre was considered “show business.” Le Gallienne longed for the government-subsidized theatres of Europe, which produced a panoply of plays at affordable prices. Having won what she called the “Battle of Broadway,” she used her fame and influence to fulfill her dream of creating a “people’s theatre.” In 1926, at the age of twenty-seven, she founded the Civic Repertory Theatre on West Fourteenth Street.

Funded entirely by private subsidy—i.e., wealthy patrons whom Le Gallienne cajoled into donating large sums—the Civic Rep sold tickets at a much lower rate than that of Broadway theatres, attracting a diverse audience and fulfilling Le Gallienne’s maxim, “The theatre should be an instrument for giving, not a machinery for getting.” As lead actor, director, and producer, she ran the company successfully for more than seven years, earning a reputation as a bold female innovator in an industry dominated by men. By 1934, however, the Depression had diminished the fortunes of the theatre’s supporters, and the Civic Rep was forced to close. For the next five decades, Le Gallienne continued working as an actor, director, and producer—on Broadway, on tour, and eventually in the regions—as well as the author of several books and new translations of Ibsen and Chekhov. But she never abandoned her quest to bring non-profit repertory theatre to the United States. When she died in 1991, Miss LeG left a legacy of innovation and artistry that would inspire future generations of theatre artists and writers—including Madeleine L’Engle and myself.

In 2016, I learned more about that legacy when I befriended the late Broadway actress Carole Shelley, who performed with Miss LeG in the 1976 national tour of Kaufman and Ferber’s comedy “The Royal Family.” After telling me many delightful stories about their work together, she lent me her signed copy of Miss LeG’s autobiography, At 33—which was so compelling, I read it in a single sitting. I had always been mystified as to why such a vital pioneer of the American theatre had fallen largely into obscurity since her death. I’d taken three semesters of Theatre History in college and never heard her name, despite the fact that the Civic Rep set the stage for the Off-Broadway and regional theatre movements that swept the country in the 1950s and ’60s. I decided to adapt the tale of Miss LeG’s early life into a stage play, using the art form she adored to introduce her to a new generation of audience members. But after three years of development, the pandemic killed all the momentum I’d been building toward production. Finally, in 2022, I met with an audiobook producer who had seen the play’s first public reading and expressed interest in turning it into an audio drama. I adapted the script, turning stage directions into sound effects and streamlining the list of characters that the five actors (including myself) were to play. This month, that audio drama, The Queen of Fourteenth Street, was released by Hachette Audio. I still hope that the play will one day be produced onstage, but in an era when live performance tickets are often prohibitively expensive, the ubiquitous medium of digital audio seems a perfect conduit for the story of a woman who wanted theatre to be accessible to everyone.

In 2016, I learned more about that legacy when I befriended the late Broadway actress Carole Shelley, who performed with Miss LeG in the 1976 national tour of Kaufman and Ferber’s comedy “The Royal Family.” After telling me many delightful stories about their work together, she lent me her signed copy of Miss LeG’s autobiography, At 33—which was so compelling, I read it in a single sitting. I had always been mystified as to why such a vital pioneer of the American theatre had fallen largely into obscurity since her death. I’d taken three semesters of Theatre History in college and never heard her name, despite the fact that the Civic Rep set the stage for the Off-Broadway and regional theatre movements that swept the country in the 1950s and ’60s. I decided to adapt the tale of Miss LeG’s early life into a stage play, using the art form she adored to introduce her to a new generation of audience members. But after three years of development, the pandemic killed all the momentum I’d been building toward production. Finally, in 2022, I met with an audiobook producer who had seen the play’s first public reading and expressed interest in turning it into an audio drama. I adapted the script, turning stage directions into sound effects and streamlining the list of characters that the five actors (including myself) were to play. This month, that audio drama, The Queen of Fourteenth Street, was released by Hachette Audio. I still hope that the play will one day be produced onstage, but in an era when live performance tickets are often prohibitively expensive, the ubiquitous medium of digital audio seems a perfect conduit for the story of a woman who wanted theatre to be accessible to everyone.

I knew when I wrote to Madeleine L’Engle thirty years ago that I wanted to be an actress and a writer when I grew up. Now that I am, it’s been thrilling to explore the connection between two of the creative artists I most admire. As Miss LeG always said, “The dead help the living.” I’m grateful for the help and inspiration I’ve received from both of these extraordinary women.

Barrie Kreinik is a writer and performer based in New York City. She is the author of the original audio drama The Queen of Fourteenth Street, released on June 4th by Hachette Audio, which tells the story of Eva Le Gallienne and the Civic Rep.

by

by