Madeleine L’Engle Biographical Sketch / Page 3 of 4

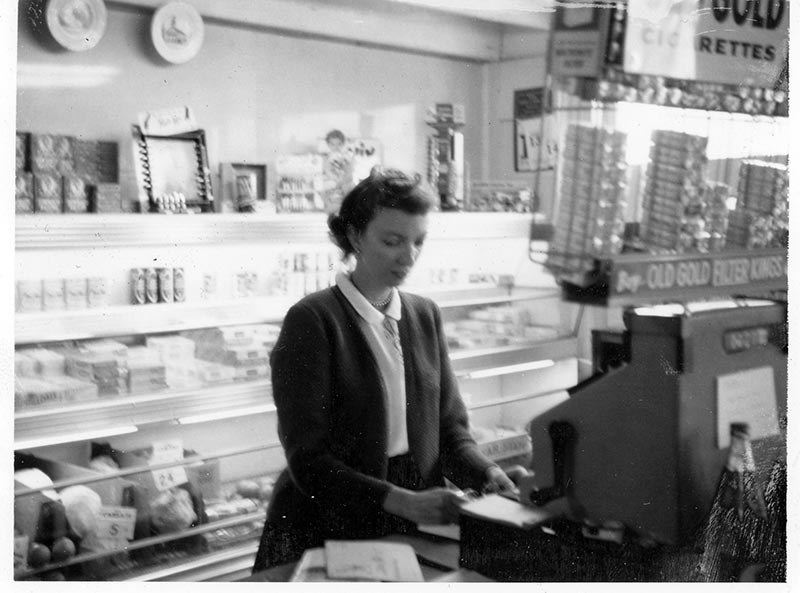

The quaint New England farming village had an old general store in need of new management–they bought that, too. Madeleine helped to run it part-time, while also being a full-time mother and part-time novelist (Camilla Dickinson, published in 1951, would land on O Magazine’s 2009 summer reading list) writing at the kitchen table in short bursts of time between toddler interruptions.

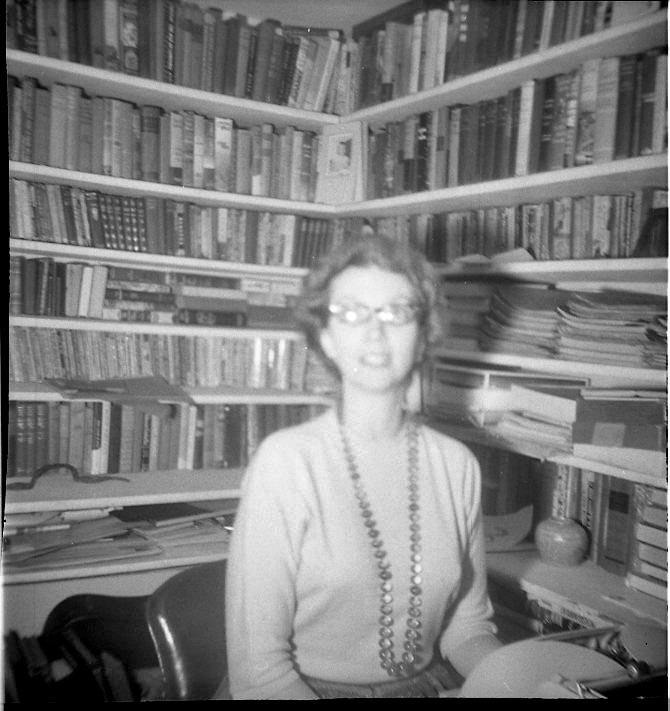

Later, she would admit that the only time her force field of silence failed her was when she had crawling toddlers. She wrote on, though, and as a housewife in the late 1950s managed to compose one of the great American novels of the 20th century.

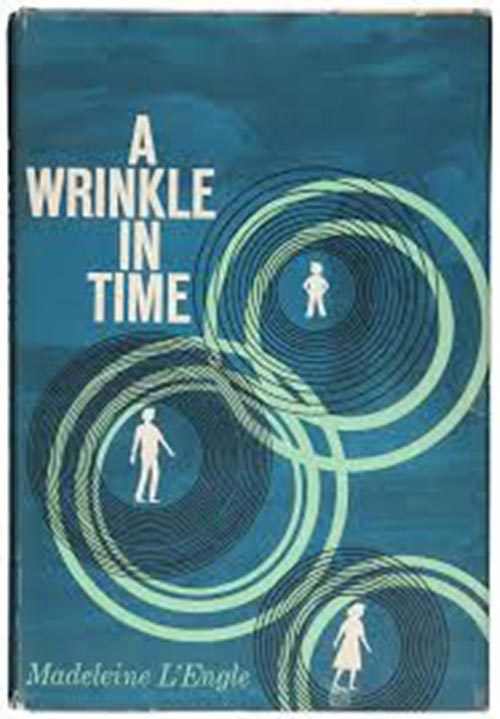

Madeleine wrote A Wrinkle in Time, so different from anything that she had written before–so different from anything that anybody had written before–after a period of doubt, when she was questioning her worth and value as both a writer who wasn’t getting published and a housewife who failed at baking pies and waxing floors. She didn’t know if she believed in God anymore, and despaired of the meaning and purpose of life. Her minister recommended she read thick theological texts. They only put her to sleep. Then Madeleine discovered a new vision of the Divine in an unlikely place–physics. She read the work of Albert Einstein, Max Planck, and Werner Heisenberg. In their writings she was reminded of her glimpse of glory as a child being shown the night sky. In their writings she saw a reverence for the beauty and laws of the universe and for the ever unfolding understanding of it. In the more than 60 books Madeleine wrote across genres, her work came to embrace the imagery and language of both science and spirituality.

A Wrinkle in Time incorporates themes that had been percolating in her diaries for years, from reflections on personal “faults” to Einstein’s writings on relativity. Around the tesseract Madeleine constructed an unconventional family living in a conventional town, a girl whose teachers underestimated her, a father who was gone too soon, and an evil that ruled by convincing people that being different was the problem. And the tesseract connected that family and that girl to an entire universe of unimaginable creatures all connected to one powerful source of Light.

“If I’ve ever written a book that says what I believe about God and the universe, this is it,” Madeleine L’Engle confided to her private journal on June 2nd, 1960.

But A Wrinkle in Time would not be published for another two years. Editors didn’t think it would sell.

“I know [this] is a good book,” Madeleine told herself, shaking off the first few snubs. “…This is my psalm of praise to life, my stand for life against death.”

The novel was not easily classifiable, and therefore not easily marketable. Madeleine and the book she believed to be her masterpiece received some 25 to 40 rejections (she revised the number with each retelling). Finally, A Wrinkle in Time found a home at the literary house of Farrar, Straus & Giroux, who published it in 1962.

A Wrinkle in Time went on to win the prestigious 1963 Newbery medal and has sold over 16 million copies in more than 30 languages, and counting.

But the attention wasn’t always positive. Given the enormous popularity of the Narnia books, especially embraced by evangelicals, Madeleine was dismayed by the outcry over A Wrinkle in Time and its four sequels. The books were controversial for their use of religion—some thought there was too much, others not enough. Conservative evangelicals lobbied for its removal from school libraries, accusing her of promoting witchcraft and “New Age-ism.” Many Christian bookstores refused to sell A Wrinkle in Time. The book now holds the distinction of being one of the most frequently banned novels in American literature.

With that, Madeleine L’Engle became one of few authors to experience enduring literary superstardom during their lifetime, and one of even fewer to live long enough—another 44 years—to see their book take root in the culture, changing the lives of generations of readers and transforming the landscape of possibility for women writers of science fiction and female protagonists. Meg Murry would become an enduring and universal symbol of adolescent angst and girl power—one of the most cherished and iconic characters in American fiction. Millions of lonely young people have felt empowered. I can fight the darkness. I am not alone.

Madeleine L’Engle (aka Mrs. Hugh Franklin), in the Goshen General Store, circa 1955.

Original cover of A Wrinkle in Time, designed by Ellen Raskin, 1962.

Madeleine L’Engle in her “Tower,” her writing room above the garage where she wrote A Wrinkle in Time, circa 1959.

Disney’s film adaptation starring Storm Reid as Meg Murry, directed by Ava Duvernay, was released in 2018.