Abigail Santamaria is working on the first fully-sourced adult biography of Madeleine L’Engle, which will be published by Farrar, Straus & Giroux, Madeleine’s publisher for more than fifty years. With this contribution in honor of the 100th anniversary of Madeleine’s birth, she gives us a brief taste of the full life story to come. It will be on the website “About” section, with photographs and memorabilia.

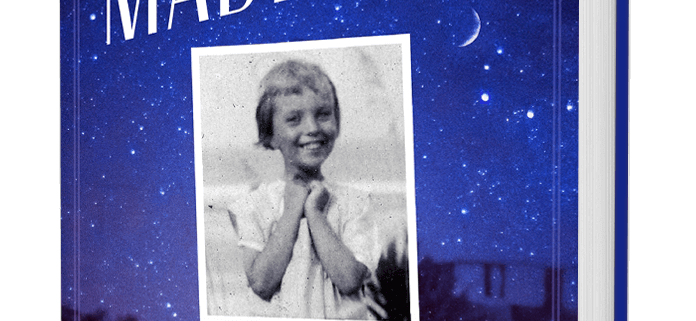

One hundred years ago, in the pre-dawn hours of November 29, 1918, Madeleine L’Engle’s mother hastily scrawled this letter to her husband, a lieutenant stationed in France: “Dearest Husband, My labor has come. I am going now to the hospital. How I long for you.”

Later that day, she gave birth to the child for whom she had yearned for 11 years, a baby girl who would grow up to become one of the most beloved American authors of the 20th century.

Madeleine’s earliest and most formative memory was being awakened from sleep and carried out to the beach on a clear, cloudless night. The expansive dark sky, the bright stars, and the sound of the waves offered a glimpse of glory, a revelation of creation and its bounty. This first glimpse of the enormity and depth of the universe would contribute to Madeleine’s understanding that science and God are not at odds — a radical and, to some, even blasphemous assertion that would appear as a theme in several of her novels, including Camilla and A Wrinkle in Time.

In the New York City of her childhood, Madeleine saw little of the stars and not enough of her parents. Born on November 29, 1918, in New York City, Madeleine was the only child of two artists — her father, Charles, was a journalist, novelist, and playwright, and her mother, also named Madeleine, a pianist. Socialites with a full calendar, Charles and Madeleine often left their daughter in the care of a housekeeper, an Irish Catholic immigrant called Mrs. O.

While young Madeleine’s parents tended to their daughter’s cultural and academic education, spiritual and emotional care was Mrs. O’s domain. “Wherever she was, there was laughter and joy, the infallible signs of the presence of God,” Madeleine wrote years later.

When she wasn’t with Mrs. O, Madeleine spent hours alone in her bedroom, where she read, wrote, and dreamed. She began writing as soon as she could hold a pencil, and when she had finished all the books on her bookshelf, she composed her own stories and poems. A few years later, her father passed down his old typewriter, which became the tool she used to write her first novels.

When Madeleine was 12, her parents moved to Europe and abruptly deposited her at the Chatelard School in Switzerland, an elite all-girls boarding school where she felt abandoned, alienated, and shattered by the loss of privacy. Surrounded by cliquish and petty peers, under the watchful eyes of school matrons, Madeleine was forced to develop a new skill: an impenetrable “force field of silence” that she could inhabit like a magical cloak. “Within that force field, I could go on writing my stories and my poems and dreaming my dreams,” she said in an interview decades later. It was an effective tool, and one that would always serve her creatively.

That experience, she would later say, helped her become a writer. And what a writer she would become.

Three years later, Madeleine and her parents moved back to the United States and, just shy of her 15th birthday, Madeleine was sent away to yet another boarding school: Ashley Hall, in Charleston, South Carolina. But unlike at Chatelard, she quickly settled in and found her niche, though making friends remained a challenge. Joining the drama club, she discovered both a love for performing and an interest in playwriting. Her dedication to writing in general became consuming. “I was born with the itch for writing in me, and o, i couldn’t stop it if i tried,” she wrote in her journal in 1934.

Madeleine’s high school years were shaken by two deaths–the first, of her grandmother, and then, more traumatically, her father’s. In the fall of 1936, shortly before her 18th birthday, Charles fell gravely ill with pneumonia. News of his hospitalization was dispatched to Ashley Hall and she was summoned to Jacksonville to say goodbye. He died before she arrived. Devastated, Madeleine made a pledge in Charles’s honor: “I have to succeed in my writing for Father’s sake as well as my own,” she wrote in her journal on December 11, 1936, “for it meant so much to him, and he just missed success by bad fortune and not enough discipline.” An absent or distant father would become a leitmotif in many of her novels, most famously in A Wrinkle in Time, whose adolescent protagonist Meg saves her father and defeats evil through love.

Madeleine went on to attend Smith College, where in 1941 she earned a B.A. in English. Newly graduated, she moved back to New York City and began a 6 year career in the theater. On Broadway and on tour, she made good use of her many hours in the wings and backstage by summoning that “force field of silence” to write a first novel — The Small Rain (Vanguard: 1945) — in snatches of time between scenes.

The New York Times called the novel “evidence of a fresh new talent,” the work of a “young actress [who had] somehow managed to compose [it] during the hurry and bustle of a road tour.” Strong, steady sales earned Madeleine a livable income for the next several years. Fourteen months after the publication of The Small Rain, Madeleine followed up with her second book, Ilsa.

It was in Eva LeGallienne’s Broadway production of “The Cherry Orchard” that Madeleine met the actor Hugh Franklin, who would become her husband in 1946. They began a family and moved to an old farmhouse in Goshen, CT. They called their new home “Crosswicks,” after the New Jersey childhood estate of Madeleine’s father, and joined the local Congregational Church.

The quaint New England farming village had an old general store in need of new management–they bought that, too. Madeleine helped to run it part-time, while also being a full-time mother and part-time novelist (Camilla Dickinson, published in 1951, would land on O Magazine’s 2009 summer reading list) writing at the kitchen table in short bursts of time between toddler interruptions.

Later, she would admit that the only time her force field of silence failed her was when she had crawling toddlers. She wrote on, though, and as a housewife in the late 1950s managed to compose one of the great American novels of the 20th century.

Madeleine wrote A Wrinkle in Time, so different from anything that she had written before–so different from anything that anybody had written before–after a period of doubt, when she was questioning her worth and value as both a writer who wasn’t getting published and a housewife who failed at baking pies and waxing floors. She didn’t know if she believed in God anymore, and despaired of the meaning and purpose of life. Her minister recommended she read thick theological texts. They only put her to sleep. Then Madeleine discovered a new vision of the Divine in an unlikely place–physics. She read the work of Albert Einstein, Max Planck, and Werner Heisenberg. In their writings she was reminded of her glimpse of glory as a child being shown the night sky. In their writings she saw a reverence for the beauty and laws of the universe and for the ever unfolding understanding of it. In the more than 60 books Madeleine wrote across genres, her work came to embrace the imagery and language of both science and spirituality.

A Wrinkle in Time incorporates themes that had been percolating in her diaries for years, from reflections on personal “faults” to Einstein’s writings on relativity. Around the tesseract Madeleine constructed an unconventional family living in a conventional town, a girl whose teachers underestimated her, a father who was gone too soon, and an evil that ruled by convincing people that being different was the problem. And the tesseract connected that family and that girl to an entire universe of unimaginable creatures all connected to one powerful source of Light.

“If I’ve ever written a book that says what I believe about God and the universe, this is it,” Madeleine L’Engle confided to her private journal on June 2nd, 1960.

But A Wrinkle in Time would not be published for another two years. Editors didn’t think it would sell.

“I know [this] is a good book,” Madeleine told herself, shaking off the first few snubs. “…This is my psalm of praise to life, my stand for life against death.” The novel was not easily classifiable, and therefore not easily marketable. Madeleine and the book she believed to be her masterpiece received some 25 to 40 rejections (she revised the number with each retelling). Finally, A Wrinkle in Time found a home at the literary house of Farrar, Straus & Giroux, who published it in 1962.

A Wrinkle in Time went on to win the prestigious 1963 Newbery medal and has sold over 16 million copies in more than 30 languages, and counting.

But the attention wasn’t always positive. Given the enormous popularity of the Narnia books, especially embraced by evangelicals, Madeleine was dismayed by the outcry over A Wrinkle in Time and its four sequels. The books were controversial for their use of religion—some thought there was too much, others not enough. Conservative evangelicals lobbied for its removal from school libraries, accusing her of promoting witchcraft and “New Age-ism.” Many Christian bookstores refused to sell A Wrinkle in Time. The book now holds the distinction of being one of the most frequently banned novels in American literature.

With that, Madeleine L’Engle became one of few authors to experience enduring literary superstardom during their lifetime, and one of even fewer to live long enough—another 44 years—to see their book take root in the culture, changing the lives of generations of readers and transforming the landscape of possibility for women writers of science fiction and female protagonists. Meg Murry would become an enduring and universal symbol of adolescent angst and girl power—one of the most cherished and iconic characters in American fiction. Millions of lonely young people have felt empowered. I can fight the darkness. I am not alone.

By then, Madeleine and Hugh had moved with their three children–Josephine, Maria, and Bion–back to New York City, to an apartment on Manhattan’s far upper west side, though they kept Crosswicks as a weekend and summer retreat. Hugh had returned to theatre life, and Madeleine carved herself a niche as volunteer librarian in the Diocesan House of the Episcopal Cathedral of St. John the Divine. There, she wrote some 25 more books, and from there she met with fans and school groups, acted as confessor and spiritual advisor to many, hosted work sessions with her editor, and coordinated occasional community outreach efforts, like writing workshops for urban teens, free at the Cathedral and taught by herself and author friends. Nearly every day she was in town, Madeleine arrived at her desk in the Episcopal Cathedral of Saint John the Divine library at 10 am, her Irish setters by her side; at noon daily, she joined others in the chapel to celebrate the Eucharist. In 2012, on what would have been Madeleine’s 94th birthday, the Cathedral’s Diocesan House was dedicated a “literary landmark” in her honor.

As the children grew, Hugh’s own career took an unexpected turn: in 1970, he was cast in the first episode of All My Children as Dr. Charles Tyler, a role he would play for the next 13 years. As a soap opera star, Hugh became more recognizable than his wife and was often approached by adoring fans for autographs when they were out and about, much to Madeleine’s amusement.

In later years, Madeleine was on the road as much as she was home in Crosswicks or her New York City apartment. She seized nearly every speaking request that came her way, honing her performance skills on literary festivals, children’s book tour circuits, schools and colleges, Christian conferences, retreats (especially for women), and churches. She beguiled audiences with props and dramatic readings, and in churches preached sermons that were “always captivating and original and yet informed by a powerful understanding of classic religion,” said her friend, the author Sidney Offit. In the second half of her life, she cultivated an enormous fan base while racking up 17 honorary doctorates, a National Book Award, and the National Humanities Medal, among many other recognitions.

After Hugh died in 1986, Madeleine’s life remained full of friends, family, and literary events. She kept to her busy speaking and writing schedule until well beyond her 80th birthday. She died on September 8, 2007 in Litchfield, Connecticut.

— Abigail Santamaria

(c) 2018 by Abigail Santamaria