“This question of the meaning of being, and dying and being, is behind the telling of stories around tribal fires at night; behind the drawing of animals on the walls of caves; the singing of melodies of love in spring, and of the death of green in autumn. It is part of the deepest longing of the human psyche, a recurrent ache in the hearts of all God’s creatures.”

— Madeleine L’Engle, Walking on Water: Reflections on Faith and Art

“Recurrent ache” is the only way to describe what I felt in my bones as I read and processed Madeleine L’Engle’s Walking on Water: Reflections on Faith and Art.

The book was published in 1972, but it didn’t find its way into my life until 2017. I was years-deep in my love for Madeleine, fueled mostly by the Time series and The Crosswicks Journals. In Madeleine I’d found a kindred spirit and a mentor. Someone who thought deeply about her faith in Jesus and wasn’t afraid to wrestle with it. Someone who saw compassion and empathy as powerful. Still today, whenever I read something she wrote, I experience what C.S. Lewis describes as friendship being born: “What! You too? I thought I was the only one.”

I don’t remember how Walking on Water landed in my lap. Did I buy it myself? Maybe someone sent it to me? Regardless, it changed my life. I’m not an artist, but I am a creator, and this book helped me understand that. As Madeleine says, “What do I mean by creators? Not only artists, whose acts of creation are the obvious ones of working with paint or clay or words. Creativity is a way of living life, no matter our vocation or how we earn our living.” And later: “God is constantly creating, in us, through us, with us, and to co-create with God is our human calling.”

I can’t tell you how much I needed to hear that.

And after hearing it, I needed even more—that’s where that recurrent ache came in—to tell people about it. Specifically, my people.

I’m a church administrator. My husband and I have been attending this church since its first service in 2006, and I came on staff almost 11 years ago. Being part of our church has been one of the most meaningful experiences of my life. The people with whom I share these pews are my family. And some members of that family are struggling to find meaning in their daily work; to figure out why their work matters; and to understand what the heck they are even doing here in the first place.

Madeleine also says this in Walking on Water: “Stories are able to help us become more whole, to become Named. And Naming is one of the impulses behind all art; to give a name to the cosmos we see despite all the chaos.”

I found myself needing to Name these friends, to bring some cosmos to the chaos they were feeling. I needed to Name their work as good.

So I gave into the impulse that Madeleine talks about. I gave in and told stories about my friends to my friends. Through a series of letters I noticed for them ways in which they are co-creators with their Maker—how they, too, are bringing cosmos to chaos in their daily work.

You can read the letters here: Cosmos to Chaos | Letters About Work. It’s my hope that in reading their stories you’ll find echoes of your own…and leave feeling a bit more whole.

Valerie Catrow is a church administrator, wife, mother, and friend who lives in Richmond, Virginia. She reads often and writes a bit. You can read some of her writing at val.catrow.net. Twitter and IG: @valeriecatrow

Valerie Catrow is a church administrator, wife, mother, and friend who lives in Richmond, Virginia. She reads often and writes a bit. You can read some of her writing at val.catrow.net. Twitter and IG: @valeriecatrow

Do you have something you’d like us to share with our blog readers? We are taking submissions for guest blog posts. Email: social [at] madeleinelengle [dot] com

My youngest daughter and I read a picture book by Madeleine L’Engle the other night. We hadn’t shared The Other Dog before, so we sat smooshed in an armchair with it, each of us holding a cover.

And we laughed: it’s a good book. The dog, Touché, L’Engle Franklin, is upset over a “new dog” in the house. Throughout the story my child was correcting Touché, interjecting some logic into this cute, silly story.

It was a good book, we decided. A good book by Madeleine’s standards; and that means something extra coming from a 7-year-old.

Kids’ reads are being feted as we speak: April 29-May 5 is the 100th anniversary of Children’s Book Week. To celebrate, we’re sharing on the blog today an essay Madeleine wrote on the subject of story and writing for kids. This piece is a banner one. “Is It Good Enough For Children?” sets up the risks of stripping the magic or truth from children’s books.

“The only standard to be used in judging a children’s book is: Is it a good book? … Because if a children’s book is not good enough for all of us, it is not good enough for children.”

She’s right, you know. From my circulation desk in an elementary school, checkouts veer toward stories (fiction or nonfiction), not dry recitation. A title called Telling the Truth (or something like that) hasn’t been checked out since I was in grade school. Meanwhile, I can’t keep Raina Telgemeier’s graphic novels on the shelf.

But declaring a kids’ book “good” requires some reading — and Children’s Book Week is a great opportunity to add to your TBR pile. Which on the lists would you call good?

Tesser well,

Erin F. Wasinger, for MadeleineLEngle.com.

P.S. Did you know that Intergalactic P.S. 3 was originally published by the Children’s Book Council for Children’s book week in 1970? This novella became A Wind in the Door.

Dear Ones,

This year for Earth Day, I went to Antarctica from my living room chair. Madeleine L’Engle brought me there, through the novel Troubling a Star.

The book, the final in the Austin Family Chronicles, opens with a teenaged, terrified Vicky clinging to an iceberg in the ocean. Before we read about any rescue operation (or even how she came to be floating alone at the bottom of the globe), we travel to the bottom of South America, to a fictitious nation with seriously sketchy plans for the icy continent. From there, Madeleine weaves a dramatic tale of danger, strange and not altogether noble characters, and a little romance. It’s great.

But more, Troubling a Star is proof that storytelling does so much more for activism, for environmentalism, for our imaginations than facts alone can.

Her story is less “here are pictures of trash in the ocean” and more “(the icebergs) seemed to have an inner light, to contain deep within their ice the fires of the sun from the days when the planet was young.” More awe, less clickbait; more feeding the imagination, less doomsday. It’s just the thesis Madeleine writes about in her nonfiction: story goes a lot farther than facts. For one, stories personify greed and then dares its heroes not to be indifferent — and so, then, the reader. Second, Troubling a Star shows us the beauty of a place most of us won’t ever go; and we’re more likely to care about a place if it’s not just an abstract idea.

In short, you could tweet lines from the book now and sound just as relevant as Madeleine did in 1994. All that’s missing are some hashtags: “Greed is always nearsighted,” and “Without our angels, I believe we would be in a worse state than we are.” And this song — how true:

All things by immortal power,

Near or far,

Hiddenly

To each other linked are,

That thou canst not stir a flower

Without troubling a star.

Madeleine visited Antarctica before writing Troubling a Star, so the details Vicky sees are legitimate. A nonfiction book was born not long after the trip, too: Penguins and Golden Calves: Icons and Idols in Antarctica and Other Unexpected Places.

What a strange thing, to visit a place where tourists just don’t go in big numbers, where animals are threatened and icebergs are melting … all because of the way we use the planet and its resources thousands of miles away. But it’s for this, I think, words she gives a scientist in Troubling a Star.

“The planet has been sending us multiple messages, and the powers that be have ignored them. So it’s up to us, and my guess is that when you finish this trip you’ll feel as protective of this amazing land as I do.”

Tesser well,

Erin F. Wasinger, for MadeleineLEngle.com.

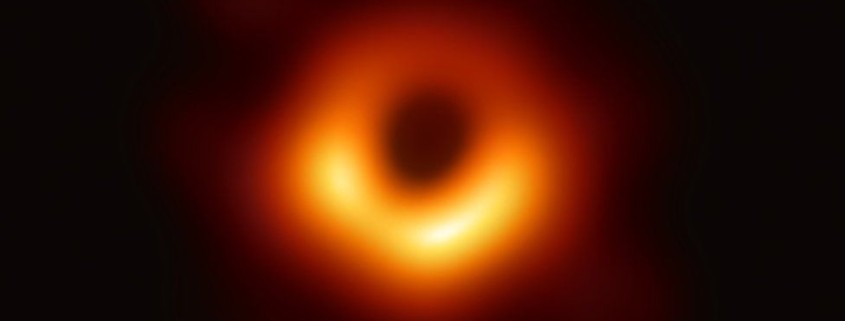

My mind went to Madeleine L’Engle last week when I saw the first picture of a black hole.

Science, astronomy, physics, quantum mechanics — all those things caught her imagination. In And It Was Good: Reflections on Beginnings, Madeleine writes about how she and her husband (Hugh Franklin) would gaze at the stars, “seeing out to the furthest reaches of space and time.” The “wild and wonderful universe” was a familiar topic in her fiction and nonfiction.

“Everything changes with every major scientific discovery,” Madeleine L’Engle said to a forum audience more than a decade ago.

She mused on black holes in that speech, which was called “Searching for Truth Through Fantasy.” “We don’t understand black holes,” she said. “But maybe if we get through one, we would come out into another universe, something quite different, yet it would still be God’s universe.”

The news was another confirmation of Albert Einstein’s theory of general relativity. As the New York Times reports, “General relativity led to a new conception of the cosmos, in which space-time could quiver, bend, rip, expand, swirl like a mix-master and even disappear forever into the maw of a black hole.” (I don’t really understand it, either.)

To Madeleine, Einstein was a theologian of the highest esteem. Madeleine often found herself defending the role of science in religion. Science “won’t do anything to change the nature of God, any more than Galileo’s discoveries changed the nature of God,” she wrote in And It Was Good.

The picture of the black hole only brings up more questions. For one thing, what happens to stuff that falls into a black hole? What’s the force in the black hole?

I think Madeleine would’ve loved it.

“I like things that do not have explanations,” she said to that audience so long ago.

Madeleine continuously spoke and wrote about the importance of asking good questions, and not being hung up on answers. For her, the mysteries of science were a window onto creation. In A Rock That Is Higher: Story as the Search for Truth, she says:

When we human creatures opened the heart of the atom we opened ourselves to the possibility of terrible destruction, but also—and we tend to forget this —- to a vision of interrelatedness and unity that can provide a theology for us to live by.

She continues later.

The discoveries made since the heart of the atom was opened have changed our view of the universe and of Creation. Our great radio telescopes are picking up echoes of that primal opening which expanded into all the stars in their courses. The universe is far greater and grander and less predictable than anyone realized, and one reaction to this is to turn our back on the glory and settle for a small, tribal god who forbids questions of any kind. Another reaction is to feel so small and valueless in comparison to the enormity of the universe that it becomes impossible to believe in a God who can be bothered with us tiny, finite creatures with life spans no longer than the blink of an eye. Or we can simply rejoice in a God who is beyond our comprehension but who comprehends us and cares about us.

The new glimpse at the universe given to us last week is a reminder to be open to revelation and to keep asking questions.

— Erin F. Wasinger for MadeleineLEngle.com.

Meg saved the world again last week in East Lansing, Michigan.

Michigan State University’s theater department transformed an intimate stage into Camazotz for the occasion, bringing to campus a stage adaptation of A Wrinkle in Time.

Photo Courtesy of Michigan State University.

This was a book-lover’s show: a tribute to the story and its truth, not a high-tech reproduction of detail-by-detail world-building.

“The reader is very present in this adaptation,” said A Wrinkle in Time director Ryan Welsh, assistant professor of theatre at Michigan State. Student actors reading copies of the Newbery Award-winning book step into and out of the imagined reality playing out on stage. Sometimes the actor-readers narrate when internal thoughts make the action go silent. Parts of this adaptation is right from the novel, dialogue verbatim.

“The cast is comprised of readers that are living in 1962 and they crack open this book and it’s through their collective conjuring of their imaginations that the story comes to life,” he said.

Tracy Young adapted the novel for the Oregon Shakespeare Festival about five years ago. The script is available through Stage Partners, along with a few other adaptations, each one suited to different cast sizes, audiences, and other needs. (To read or download the script, see Stage Partners’ Wrinkle in Time page here.) Theater troupes from Seattle Pacific University to a community group in Australia will perform Young’s play in the next year.

In Michigan State’s production, the audience had an intimate spot. Every scene from the Murrys’ house to Camazotz and back were performed in a round, and entering the theater was an immersion in the production before it even began.

A man in a red flannel shirt swept a part of the stage, surprising some of us by later playing Fortinbras the dog, among other roles. A student sat at a stool, reading from a big book. A woman held up paint swatches to a pillar in the corner of the stage, then “painted the wall” with a dry brush. A boy dressed like a teen from the ‘60s bounced a basketball just off stage; a woman lingered by the stove.

All this happened while audience members were finding seats, using the restroom, finishing snacks. Unless one was paying attention, the cast’s comings and goings could be mistaken for the normal comings and goings of an excited crowd.

Eventually, they all settled in scattered spots around the room, reading copies of A Wrinkle in Time. The lights dimmed; the play began.

How do you create a magical, otherworld on stage (without the budget behind, say, The Cursed Child)? Welsh used the “sandbox idea”: they used what they had and let imaginations take over the rest. The narrative was entrancing enough. The movement-driven, ever-changing ensemble cast made the play soar. Somehow, the low-key components — Aunt Beast, the act of tessering, even IT — were more engrossing because they lacked flashiness.

When they needed a dog, one of the actors crouched with an origami-looking dog’s head in one hand. When they needed to convey tessering, lights did the heavy lifting. A white sheet became the Brain. Best, most convincing, was Charles Wallace under IT’s power. Inspired by a Japanese dance theater move called Butoh, his shoulders, neck, knees all moved in odd, jerky, horrific ways, amping up the terror for the audience.

My copy of A Wrinkle in Time suggests that readers be 10 or older; the play had the same recommendation. Though Wrinkle is considered children’s literature, Welsh said he didn’t want to do a play for kids. Instead, his philosophical approach was to let the actors create an illusion that would let the audience’s imaginations take over.

Welsh, who has a film background, said he knew the danger of adapting a well-loved book for the stage — especially this one, what he called the “grandmother of young adult fiction.”

“There’s so much credit owed and due to that book,” he said. So he didn’t want to simply tell the story; he wanted the audience to join actors on the adventure.

A Wrinkle in Time on stage “invites (the audience) to engage with it in order for (the story) to feel valid, magical and special and all the things we want it to feel,” he said. Magical and special aren’t usually words reserved for grown-up theater, but Welsh said they should be.

“(We adults are) so wrapped up in the grind that we forget how to fantasize,” he said. This adaptation says, “Come, imagine with us, in a similar way a book does.”

I felt that permission to let my imagination romp around during the production. Right after landing in the twins’ vegetable garden, right before the cast bows, a small, holy spell hung in the air. Meg may have saved the world, but the audience? We tessered right with her.

— Erin F. Wasinger, for MadeleineLEngle.com.

Dear Ones,

A new teachers’ guide is out, inspiring deeper conversations around the book Becoming Madeleine: A Biography of the Author of A Wrinkle in Time by her Granddaughters.

The unit is perfect for encouraging students to think critically about artists, their work, and childhood influences. The book lends itself to reflecting on Madeleine L’Engle herself in a unique way. Charlotte Jones Voiklis and Léna Roy’s book is unlike boring, dry biographies that are often foisted on young readers. Instead, Becoming Madeleine includes never-before-shared pictures, letters, diary entries, and insight only Madeleine’s granddaughters could tell.

The teachers’ guide takes the learning a step further by relating Madeleine’s life to her legacy and her work. Questions and writing prompts spark some critical thinking (and meet Common Core standards, which you can tweak til your heart’s content to fit your audience). Here’s a couple, for example:

- Though she could be social, Madeleine struggled with peer relationships periodically and spent a great deal of time in her own head, dreaming of stories. How might doing this help create a storyteller?

- Throughout the biography, readers learn that while trying to excel at her craft, Madeleine reaches out to published poets and authors. What can readers infer about her based on these actions?

Aspiring young authors and new fans of L’Engle (especially those middle-grade readers) can be encouraged in the discussions, too, to reflect on their own lives and work. Ooh. So good, right?

The guide is free, just like the guide for A Wrinkle in Time; both compliments of Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, an imprint of Macmillan Children’s Publishing Group. Let us know how you’re using them in classroom! We’d love to hear about what it’s inspired.

Tesser well,

— Erin F. Wasinger, for madeleinelengle.com.

P.S. The ebook is on sale through the end of March 2019!

Dear Ones,

We’re happy to share that a new A Wrinkle in Time teacher resource has arrived! Get your copy of the free resource here, compliments of Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, an imprint of Macmillan Children’s Publishing Group.

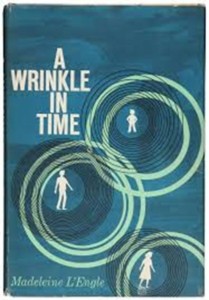

A Wrinkle in Time, the winner of the 1963 Newbery Medal and many young readers’ first encounter with Madeleine’s work, celebrated its 50th anniversary in 2013. It continues to rock the socks off its first-time readers, as teachers and school librarians can attest.

I (Erin) remember first reading A Wrinkle in Time as a middle-schooler. I can still picture my school’s copy with its blue cover, colliding circles, and white silhouettes. The sides of its pages were worn smooth by readers before me (a quiet endorsement in a school library). I loved the story and was confused all at once, pouring over its pages from the dark and stormy night to Meg’s return home. Most memorable, though, was my impulse to talk about the book with my friends: I simply had to.

I (Erin) remember first reading A Wrinkle in Time as a middle-schooler. I can still picture my school’s copy with its blue cover, colliding circles, and white silhouettes. The sides of its pages were worn smooth by readers before me (a quiet endorsement in a school library). I loved the story and was confused all at once, pouring over its pages from the dark and stormy night to Meg’s return home. Most memorable, though, was my impulse to talk about the book with my friends: I simply had to.

Preteens in conversation … about a book? Now that’s the highest form of praise.

This new teachers’ guide can inspire that sort of magic, too. You’ll find great prompts for classroom discussions and essay-writing, STEM-related stuff, plus activities that range from exploring themes to exploring space. Questions related to the eponymous 2018 movie (directed by Ava Duvernay) are included, too. Icing on the cake: citations for Common Core alignment. Boom.

Find this new resource — and other A Wrinkle in Time resources — on the educators’ page.

Oh, one more thing: Are you using A Wrinkle in Time in your classroom? Are your students writing amazing essays or doing creative projects? Let us know! We’ll recognize outstanding student work — and the teachers who make that possible — with a blog post and swag! Please contact charlotte [at] madeleinelengle [dot] com.

Tesser well,

— Erin F. Wasinger, for madeleinelengle.com.

Dear Ones,

Audiobook lovers, rejoice! New audio editions of Madeleine’s Austin Family Chronicles series are out in the world, through Penguin Random House Audio. These make a great listen for middle-grade or YA readers (or any of us who wished we were Austins).

The five books in the Austin Family series follow Vicky Austin as she navigates growing up. Incredibly, the voice actor in this new edition captures this progression: listen to Jorjeana Marie’s talents yourself in previews of the first and final books: Meet the Austins and Troubling a Star. (Pretty cool, right?)

Madeleine L’Engle, circa 1984. Courtesy of Sea World San Diego, by Eva C. Ewing.

Fun fact: Did you know that we celebrated new additions to the series for more than 30 years? Madeleine first published Meet the Austins in 1960, followed by The Moon By Night in ‘63, and The Young Unicorns in ‘68. It wasn’t until 1980 that Newbery Honor book A Ring of Endless Light landed on the scene. Troubling a Star completed the series in 1994.

Happy listening,

— Erin F. Wasinger, for madeleinelengle.com.

P.S. — And don’t miss audiobooks from the Time Quintet — read by Madeleine herself! Click here for those.

Dear Ones,

Listening to Madeleine L’Engle read A Wrinkle in Time is nothing short of captivating.

Hear for yourself: It was a dark and stormy night, she begins, with not an ounce of sentimentality. Hooking the listener with her passionate cadence in this opening scene, the audio narration continues: In her attic bedroom Margaret Murry, wrapped in an old patchwork quilt, sat on the foot of her bed and watched the trees tossing in the frenzied lashing of the wind. When Meg shakes, I shook, sensing the storm that opens A Wrinkle in Time.

Listening to the audio in the author’s voice is a gift, available now thanks to restored recordings Penguin Random House Audio. Penguin Listening Library’s versions come from recordings done from 1993 to 1996 of A Wrinkle in Time, A Wind in the Door, and A Swiftly Tilting Planet. Sample and purchase the recordings here:

A Wrinkle in Time, or listen on Audible;

A Wind in the Door, or listen on Audible;

A Swiftly Tilting Planet, or listen on Audible.

Happy listening!

— Erin F. Wasinger, for madeleinelengle.com.

Ken Lewis

Ken Lewis

Michigan State University

Michigan State University