by Jessica Kantrowitz

Well, dear ones, 2022 has been a bit of a year already, hasn’t it? I’m not going to write, here, about all the things that have been going on, in the world, in America, in my own small circles, but I will say that it is a lot. I don’t know anyone who isn’t reeling from the steady stream of bad news—epidemiologically, politically, and otherwise. It’s overwhelming and exhausting. Many of us are burnt out, or well beyond burnt out. Many of us are angry and outraged. Anger is an entirely rational, appropriate response to so many of the things happening in the world right now.

But it’s not the only appropriate response.

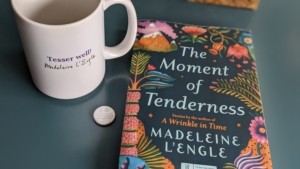

If you’re like me, you’ve probably heard the expression, “If you’re not angry, you’re not paying attention.” It’s so ubiquitous these days that my Googling attempts to find the original author just came up with pages and pages of unattributed quotes. (But let me know if you know!) A nd if you’re here at the Madeleine L’Engle blog, you’re most likely familiar with the quote from A Wrinkle in Time:

nd if you’re here at the Madeleine L’Engle blog, you’re most likely familiar with the quote from A Wrinkle in Time:

“Stay angry, little Meg,” Mrs Whatsit whispered. “You will need all your anger now.”

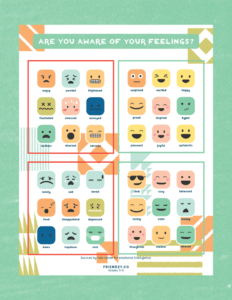

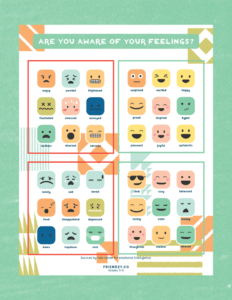

But is anger the only byproduct of paying attention? I don’t know. I think paying attention can trigger all manner of emotions and reactions. Fear, overwhelm, sorrow, hopelessness—even joy and hope. Anger is a useful motivator, sure, but all our feelings tell us something, give us insight into ourselves and the world around us.

If you feel angry—that’s appropriate! If you feel despair—that makes sense. If you feel joy because you’ve worked so hard to heal your mental health and are finally in a good place, and cannot let yourself be pulled into that pit again, even by national crisis—that’s valid. Joyful people can work for change, too. Sad people can make a difference in the world. Angry people can use their anger as fuel—but there are other fuels, too.

When Mrs. Whatsit told Meg to stay angry, that was because that was Meg’s particular weakness-turned-strength. It was what she told Meg the first time Meg went to Camazotz, and it was in contrast to what her principal, Mr. Jenkins had said to her when she got in trouble at school:

“Try to be a little bit less antagonistic. Maybe your work would improve if you were a little more tractable.

If you’re not familiar with the somewhat old-fashioned word tractable it means, “easy to control or influence.” This, Mr. Jenkins said, would help her get along at school, but it was the exact opposite of what she would need to resist the mind control of the evil being IT. Meg’s anger and intractability were seen, by her teachers and herself, as faults, but Mrs Whatsit gave them back to her as a gift:

said, would help her get along at school, but it was the exact opposite of what she would need to resist the mind control of the evil being IT. Meg’s anger and intractability were seen, by her teachers and herself, as faults, but Mrs Whatsit gave them back to her as a gift:

“Meg, I give you your faults.”

“My faults!” Meg cried.

“Your faults.”

Meg’s anger, her antagonism, her intractability (all things, incidentally, that women are told much more frequently than men are their faults) were her gifts.

But those were the gifts given to Meg, not to Calvin, or Charles Wallace, or to Mrs. Murry or Mr. Murry, or the twins. Calvin was given his ability to communicate, and Charles Wallace was given the resilience of his childhood. Mr. and Mrs. Murry, and the twins Sandy and Dennys weren’t explicitly given gifts, but we see them play out in the series: Mrs. Murry’s quiet patience and trust, Mr. Murry’s willingness to risk his life for what he believes in, Sandy and Dennys’ loyalty and dependability. You and I might be given something else, a particular talent, or hard-won wisdom, or a different fault-turned-strength. Anger at injustice is a gift, but there are other gifts. Perhaps the most important thing we can do is acknowledge our feelings without judgment, to let them tell us what they’re there to tell us.

Author and therapist Krispin Mayfield recently tweeted:

“In unhealthy families, certain emotions aren’t allowed. We have to choose between connection with our parent OR expressing anger, sadness, worry (whatever emotion isn’t allowed). The same often happens in churches, & with good reason, we end up believing the same about God.”

But what if all emotions were allowed, and even welcomed, in our families, in our communities, in our churches and mosques and synagogues? What if our weaknesses were our strengths, both individually and because we supported and complemented each other in community?

When Meg goes to face IT for the second time, to save her beloved little brother, Mrs Who quotes the King James Bible (1 Corinthians, though she doesn’t give a reference):

But God hath chosen the foolish things of the world to confound the wise; and God hath chosen the weak things of the world to confound the things which are mighty; And base things of the world, and things which are despised, hath God chosen, yea, and things which are not, to bring to nought things that are.

The more we pay attention in our lives, the more we realize this to be true, that the weak things have strength the mighty things don’t understand, that when we look for where God is moving, where the energy and hope is, we have to look among the marginalized, among the despised, among those left out and forgotten, and not among those with power and privilege. We pay attention and we get angry, or we pay attention and we get sad, or we pay attention and we feel numb and overwhelmed, or we pay attention and we compartmentalize and allow ourselves to be renewed by hope and joy. We pay attention, and we let ourselves feel what we feel.

And then, angry, scared, grieving, joyful, overwhelmed, hope-filled, despairing, intractable—we work together to make the world a better place.

Jessica Kantrowitz

Jessica Kantrowitz is the author of several books of prose and poetry, including The Long Night and 365 Days of Peace, and the creator of the Finding Your Voice Writing Workshop (next one starts October 7!). She lives in Boston in the fall (and in the other seasons, too, but fall’s her favorite). More at www.jessicakantrowitz.com.

nd if you’re here at the Madeleine L’Engle blog, you’re most likely familiar with the quote from A Wrinkle in Time:

nd if you’re here at the Madeleine L’Engle blog, you’re most likely familiar with the quote from A Wrinkle in Time: said, would help her get along at school, but it was the exact opposite of what she would need to resist the mind control of the evil being IT. Meg’s anger and intractability were seen, by her teachers and herself, as faults, but Mrs Whatsit gave them back to her as a gift:

said, would help her get along at school, but it was the exact opposite of what she would need to resist the mind control of the evil being IT. Meg’s anger and intractability were seen, by her teachers and herself, as faults, but Mrs Whatsit gave them back to her as a gift:

In October, FSG is publishing a new picture book biography of Madeleine,

In October, FSG is publishing a new picture book biography of Madeleine,

Farrar, Straus and Giroux children’s book press, Ariel, took a chance. Sixty years later, there have been 16 million copies in 40 languages. It has been made a movie twice and a graphic novel. In May 2022, I am to enjoy it as a theatrical production by the Goshen Players in the Old Town Hall. But we were not to know any of this.

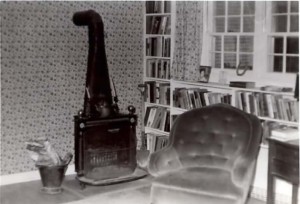

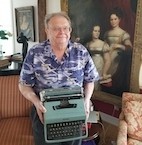

Farrar, Straus and Giroux children’s book press, Ariel, took a chance. Sixty years later, there have been 16 million copies in 40 languages. It has been made a movie twice and a graphic novel. In May 2022, I am to enjoy it as a theatrical production by the Goshen Players in the Old Town Hall. But we were not to know any of this. Tom Allison is a retired Congregational Minister living in Albany NY. Rehabbing a house once owned by a Hudson River Steamboat Captain inspired his looking into that history culminating in Hudson River Steamboat Catastrophes Contests and Collisions (History Press 2013) available Barnes and Noble and Amazon. Since 5th grade he has enjoyed offering to the public illustrated history lectures. Among the 40 plus have been American Cookbooks, plumbing,, transatlantic steamboat travel in the golden age, Litchfield Connecticut: America’s most historic mile and A neighbor remembers Madeleine L’Engle, (for the 100th anniversary of her birth) to name a few. He is pictured here at Crosswicks, with the typewriter Madeleine gave him on the occasion of his high school graduation.

Tom Allison is a retired Congregational Minister living in Albany NY. Rehabbing a house once owned by a Hudson River Steamboat Captain inspired his looking into that history culminating in Hudson River Steamboat Catastrophes Contests and Collisions (History Press 2013) available Barnes and Noble and Amazon. Since 5th grade he has enjoyed offering to the public illustrated history lectures. Among the 40 plus have been American Cookbooks, plumbing,, transatlantic steamboat travel in the golden age, Litchfield Connecticut: America’s most historic mile and A neighbor remembers Madeleine L’Engle, (for the 100th anniversary of her birth) to name a few. He is pictured here at Crosswicks, with the typewriter Madeleine gave him on the occasion of his high school graduation.