by Sarah Arthur

Extended family is on my mind this time of year. Not only is Thanksgiving around the corner, but also I recently helped co-direct the L’Engle Writing Retreat in Litchfield, CT, mere miles from Madeleine’s beloved farmhouse, Crosswicks.

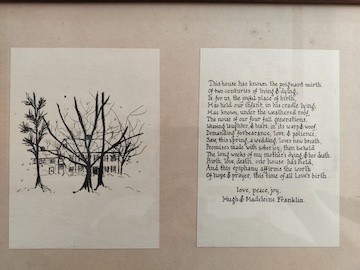

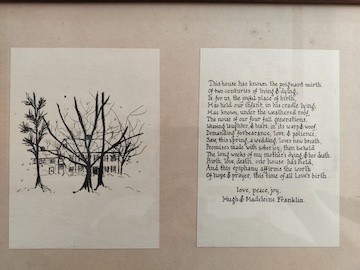

The rambling, 250-year-old building has been the private residence for many generations of Madeleine’s family since the 1940s. It plays a key role in her works: from the memoir-esque Crosswicks Journals (such as A Circle of Quiet and The Summer of the Great-Grandmother) to various fiction series for tweens and teens. Indeed, a signature theme in Madeleine’s fiction is the presence of large, multigenerational families all under one roof.

The rambling, 250-year-old building has been the private residence for many generations of Madeleine’s family since the 1940s. It plays a key role in her works: from the memoir-esque Crosswicks Journals (such as A Circle of Quiet and The Summer of the Great-Grandmother) to various fiction series for tweens and teens. Indeed, a signature theme in Madeleine’s fiction is the presence of large, multigenerational families all under one roof.

The Murrys in A Wrinkle in Time are the best-known example, of course. A house like Crosswicks is the setting that bookends the Newbery winner, hosting no fewer than four siblings, multiple pets, classmates, neighbors, alien creatures, and even angels. One of Wrinkle’s sequels, A Swiftly Tilting Planet, depicts the family gathered at the farmhouse on Thanksgiving weekend. Meg Murry (Wrinkle’s teen protagonist) is now a young woman, married to her friend Calvin and pregnant with their first child; while her youngest brother, Charles Wallace, must time-travel across continents and cultures to fulfill a prophetic rune delivered by Meg’s mother-in-law. It’s a big family story par excellence.

An adjacent series known as The Austin Family Chronicles features a similarly large cast (minus the intergalactic beings), which grows with each successive story. In Meet the Austins, the family adds a newly-orphaned child to the household, while in A Ring of Endless Light the grandfather’s terminal illness sets the stage for the extended family’s reckoning with death and dying. Here, too, everyone is under one roof.

This emphasis on multigenerational relationships is something I’ve always loved about Madeleine’s books. When I was a young child, my nuclear family lived with my grandparents for several years while my father was in graduate school. Their home was a busy hub, filled to the brim, especially at the holidays. Perhaps that’s why, during middle and high school, I was drawn to fictional characters like Meg Murry and Vicky Austin: because my earliest memories were shaped by a household like theirs.

What I didn’t realize, as a young reader, is just how unusual such stories are.

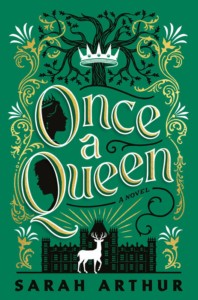

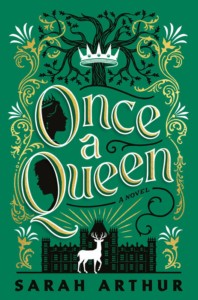

For one, it’s tough to pitch multigenerational plots to a publishing industry that often segregates audiences by age–e.g., Middle Grade (MG) for ages 8-12, Young Adult (YA) for ages 13-18, etc. My own forthcoming novel Once a Queen, which releases Jan. 30, began as YA in conversations with one publisher, but then morphed into MG when the sales team questioned the target readership. YA books, as a genre, are “issues-driven,” whereas my story features a fourteen-year-old girl named Eva who must navigate generational wounds passed down from grandmother to mother to daughter. Eventually my agent pitched the book to a different publisher as “Young Teen” (we coined the term, we think!), which did the trick. However, since “YT” is not an industry category, Once a Queen will release as YA.

For one, it’s tough to pitch multigenerational plots to a publishing industry that often segregates audiences by age–e.g., Middle Grade (MG) for ages 8-12, Young Adult (YA) for ages 13-18, etc. My own forthcoming novel Once a Queen, which releases Jan. 30, began as YA in conversations with one publisher, but then morphed into MG when the sales team questioned the target readership. YA books, as a genre, are “issues-driven,” whereas my story features a fourteen-year-old girl named Eva who must navigate generational wounds passed down from grandmother to mother to daughter. Eventually my agent pitched the book to a different publisher as “Young Teen” (we coined the term, we think!), which did the trick. However, since “YT” is not an industry category, Once a Queen will release as YA.

This insistence on pegging audiences by age was particularly frustrating to Madeleine. When asked about her proposed readership for Wrinkle, she protested, “It’s for people! Don’t people read books?” In time, she embraced the role of children’s author by claiming, “If a book will be too difficult for adults, then you write it for children”–which was her way of both affirming young people and critiquing the industry that forced her to choose.

Another challenge is that it’s hard not to engage MG/YA stories from the perspective of the adult characters. After all, as adults ourselves, the grownups are the ones to whom we relate best. And yet, they’re often unreliable participants in the child’s world, creating expectations the child can’t meet and/or vice versa. While writing Once a Queen, for instance, I had to continuously ask myself, How is Eva feeling right now? What does she need? I tried to keep in mind Madeleine’s statement, “I am still every age that I have been. Because I was once a child, I am always a child. Because I was once a searching adolescent, given to moods and ecstasies, these are still part of me, and always will be…”

Yet another challenge to big family stories is this: The more one adds siblings, grownups, friends, neighbors, and side characters, the tougher it is to keep everyone’s unique personhood at play. This is as true in real life as in fiction! I’m currently writing the sequel to Once a Queen, featuring the four siblings of Eva’s best friend, Frankie–plus a host of local villagers and an entire cast from a magical world. The deeper I get, the harder it is to keep everyone from becoming flattened tropes and plot devices. How will I bring all these relational conflicts to a satisfying conclusion? Many of us might ask the same while sitting down for Thanksgiving dinner.

I’m thankful that Madeleine gave us glimpses of how compelling intergenerational relationships can be. Teens aren’t just interested in contemporary “issues”: they also negotiate complex, multifaceted family relationships on a daily basis. They inhabit crowded stories in real life. Thanksgiving, in particular, is the annual backdrop for much of the stresses, challenges, and overall drama that shapes households, for better or worse.

While we might not live in places like Crosswicks, stories that echo family realities can give all of us–young and old alike–tools for navigating those spaces with creativity and grace.

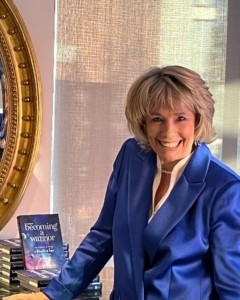

Sarah Arthur is the award-winning author of numerous books, including A Light So Lovely: The Spiritual Legacy of Madeleine L’Engle. Her YA novel Once a Queen debuts Jan. 30, 2024 from Waterbrook/Penguin Random House, which is offering exclusive perks for those who preorder. Learn how to download Ch. 1-3, plus a printable journal full of creativity prompts, quotes, and original sketches, at www.saraharthur.com.

Sarah Arthur is the award-winning author of numerous books, including A Light So Lovely: The Spiritual Legacy of Madeleine L’Engle. Her YA novel Once a Queen debuts Jan. 30, 2024 from Waterbrook/Penguin Random House, which is offering exclusive perks for those who preorder. Learn how to download Ch. 1-3, plus a printable journal full of creativity prompts, quotes, and original sketches, at www.saraharthur.com.

by

by

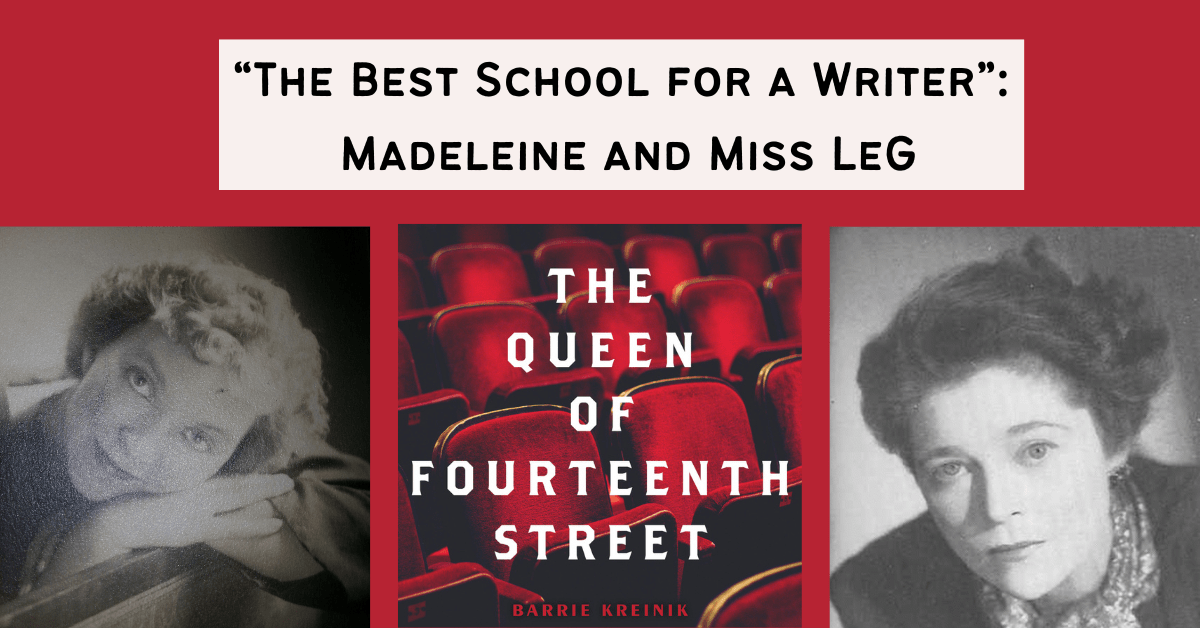

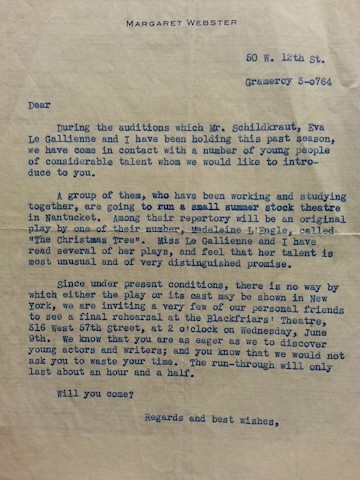

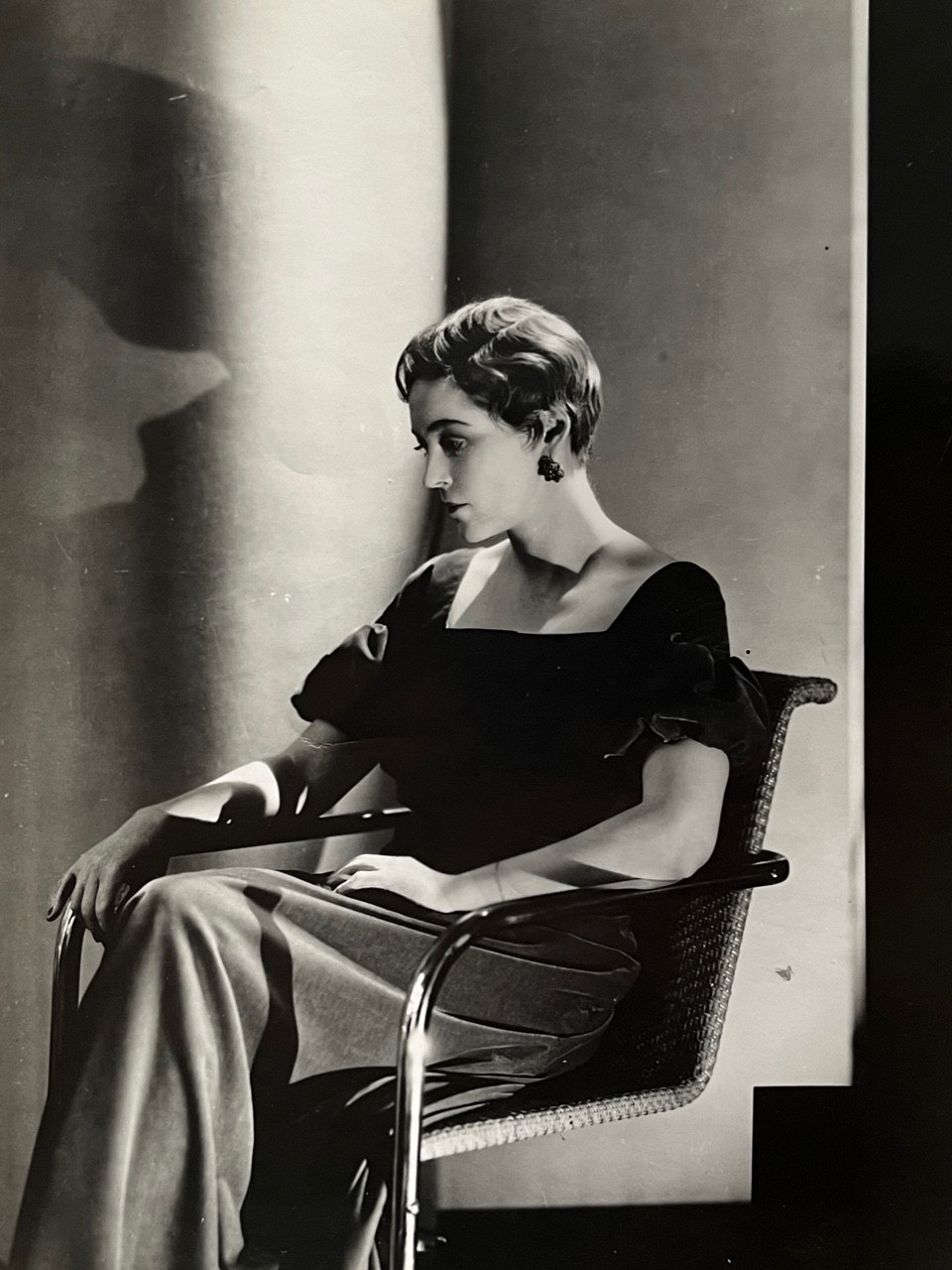

then partner, the director Margaret Webster. In 1943, Webster invited a group of theatre professionals to a reading of Madeleine’s play The Christmas Tree, writing, “Miss LeGallienne and I have read several of her plays, and feel that her talent is most unusual and of very distinguished promise.” Madeleine fulfilled that promise in 1944 when she penned her first novel, The Small Rain, inspired by her theatrical adventures with Miss LeG and written in the wings of the touring production of “Uncle Harry.” Though she soon transitioned fully from playwriting to novel writing, Madeleine would later assert that the theatre was “the best school for a writer,” and the time she spent in Miss LeG’s inner circle would remain a treasured memory.

then partner, the director Margaret Webster. In 1943, Webster invited a group of theatre professionals to a reading of Madeleine’s play The Christmas Tree, writing, “Miss LeGallienne and I have read several of her plays, and feel that her talent is most unusual and of very distinguished promise.” Madeleine fulfilled that promise in 1944 when she penned her first novel, The Small Rain, inspired by her theatrical adventures with Miss LeG and written in the wings of the touring production of “Uncle Harry.” Though she soon transitioned fully from playwriting to novel writing, Madeleine would later assert that the theatre was “the best school for a writer,” and the time she spent in Miss LeG’s inner circle would remain a treasured memory.

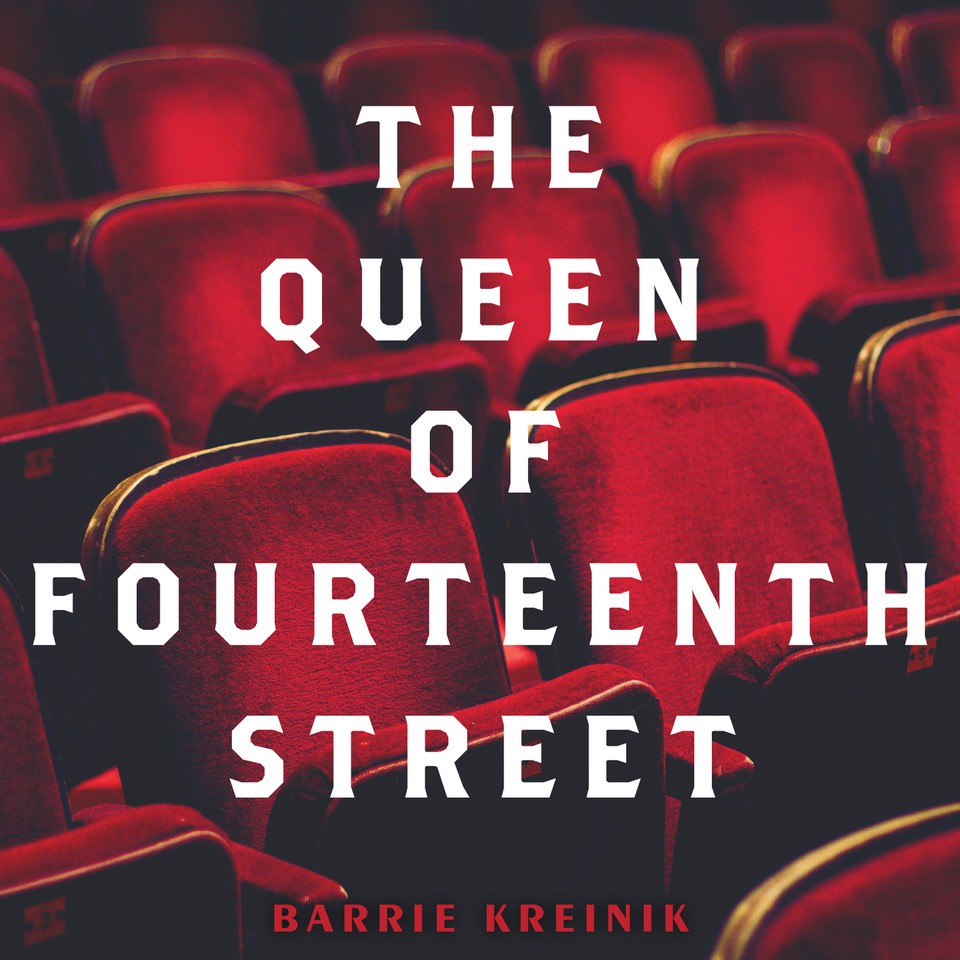

In 2016, I learned more about that legacy when I befriended the late Broadway actress Carole Shelley, who performed with Miss LeG in the 1976 national tour of Kaufman and Ferber’s comedy “The Royal Family.” After telling me many delightful stories about their work together, she lent me her signed copy of Miss LeG’s autobiography, At 33—which was so compelling, I read it in a single sitting. I had always been mystified as to why such a vital pioneer of the American theatre had fallen largely into obscurity since her death. I’d taken three semesters of Theatre History in college and never heard her name, despite the fact that the Civic Rep set the stage for the Off-Broadway and regional theatre movements that swept the country in the 1950s and ’60s. I decided to adapt the tale of Miss LeG’s early life into a stage play, using the art form she adored to introduce her to a new generation of audience members. But after three years of development, the pandemic killed all the momentum I’d been building toward production. Finally, in 2022, I met with an audiobook producer who had seen the play’s first public reading and expressed interest in turning it into an audio drama. I adapted the script, turning stage directions into sound effects and streamlining the list of characters that the five actors (including myself) were to play. This month, that audio drama, The Queen of Fourteenth Street, was released by Hachette Audio. I still hope that the play will one day be produced onstage, but in an era when live performance tickets are often prohibitively expensive, the ubiquitous medium of digital audio seems a perfect conduit for the story of a woman who wanted theatre to be accessible to everyone.

In 2016, I learned more about that legacy when I befriended the late Broadway actress Carole Shelley, who performed with Miss LeG in the 1976 national tour of Kaufman and Ferber’s comedy “The Royal Family.” After telling me many delightful stories about their work together, she lent me her signed copy of Miss LeG’s autobiography, At 33—which was so compelling, I read it in a single sitting. I had always been mystified as to why such a vital pioneer of the American theatre had fallen largely into obscurity since her death. I’d taken three semesters of Theatre History in college and never heard her name, despite the fact that the Civic Rep set the stage for the Off-Broadway and regional theatre movements that swept the country in the 1950s and ’60s. I decided to adapt the tale of Miss LeG’s early life into a stage play, using the art form she adored to introduce her to a new generation of audience members. But after three years of development, the pandemic killed all the momentum I’d been building toward production. Finally, in 2022, I met with an audiobook producer who had seen the play’s first public reading and expressed interest in turning it into an audio drama. I adapted the script, turning stage directions into sound effects and streamlining the list of characters that the five actors (including myself) were to play. This month, that audio drama, The Queen of Fourteenth Street, was released by Hachette Audio. I still hope that the play will one day be produced onstage, but in an era when live performance tickets are often prohibitively expensive, the ubiquitous medium of digital audio seems a perfect conduit for the story of a woman who wanted theatre to be accessible to everyone.

For one, it’s tough to pitch multigenerational plots to a publishing industry that often segregates audiences by age–e.g., Middle Grade (MG) for ages 8-12, Young Adult (YA) for ages 13-18, etc. My own forthcoming novel

For one, it’s tough to pitch multigenerational plots to a publishing industry that often segregates audiences by age–e.g., Middle Grade (MG) for ages 8-12, Young Adult (YA) for ages 13-18, etc. My own forthcoming novel  Sarah Arthur is the award-winning author of numerous books, including

Sarah Arthur is the award-winning author of numerous books, including

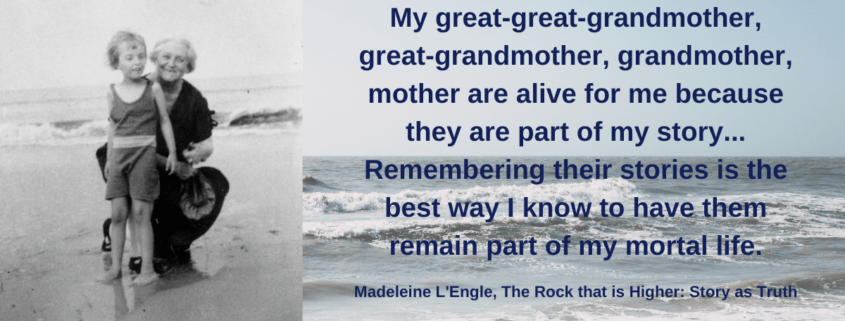

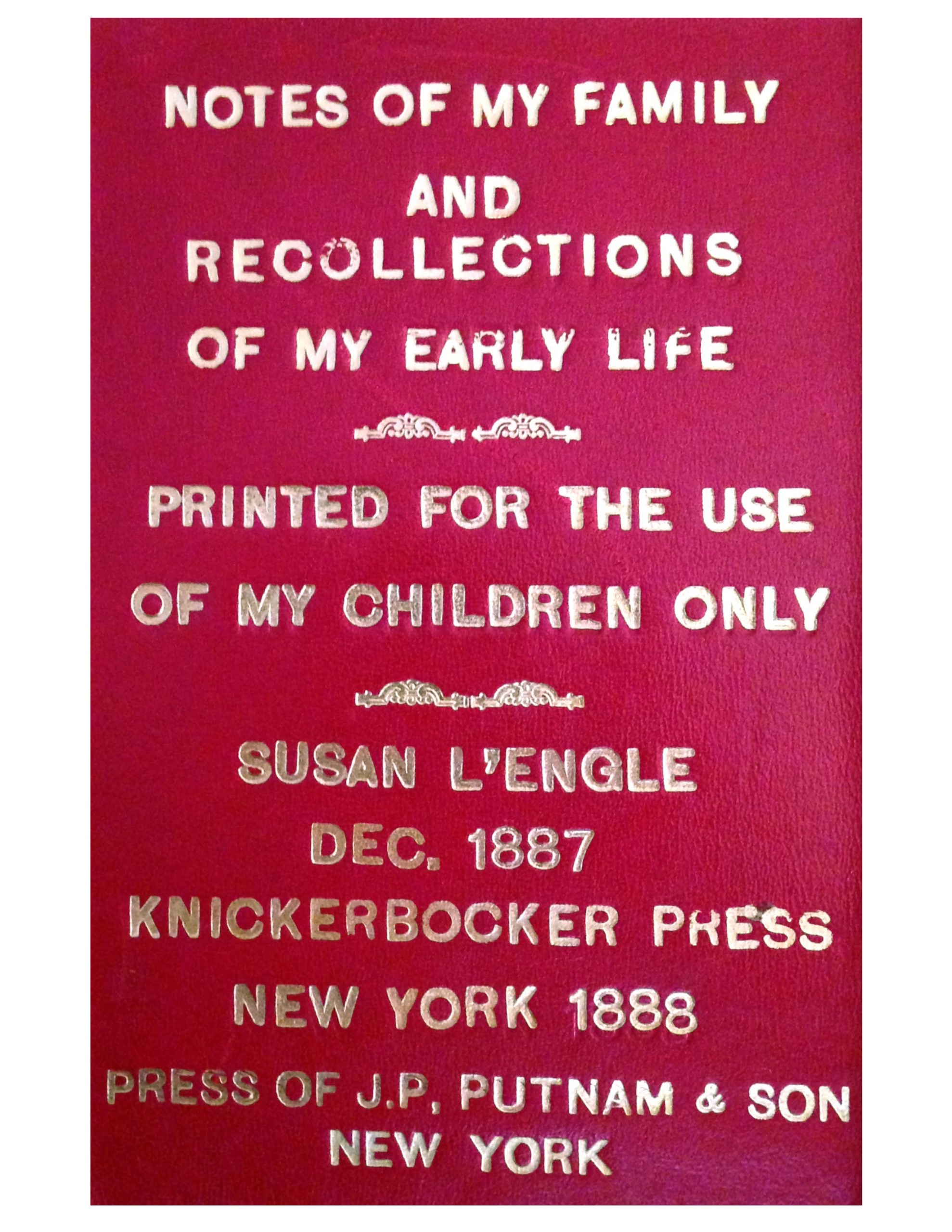

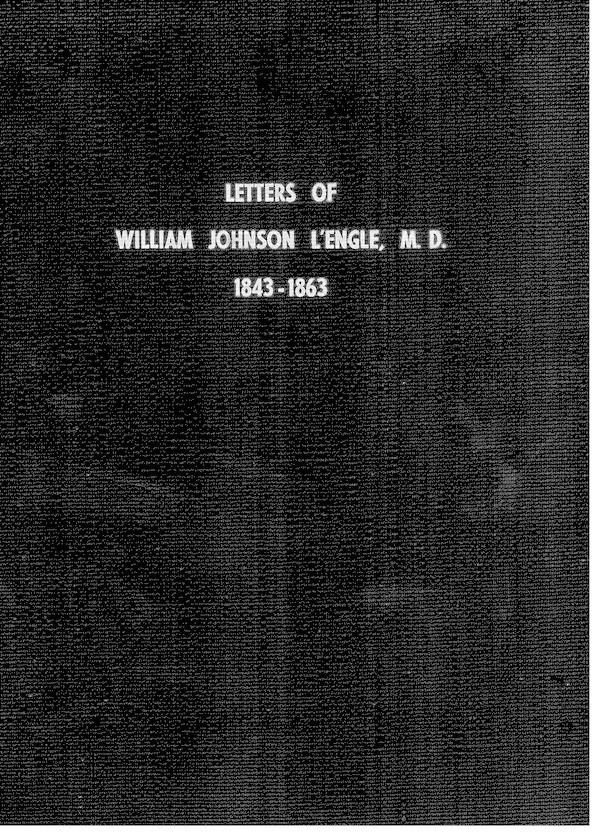

There were other stories, too, about other ancestors who anchored her to a continuum. As Madeleine’s biographer, I’ve read them all. Madeleine’s family tree flowered opulently, lush with lore and Americana, in all its triumphs and sins: Old World origin stories, one-way voyages across the Atlantic, a fateful shipwreck, colonialism, slavery, Revolutionary and Civil wars among smaller scuffles, westward pioneering, and American bootstraps prosperity.

There were other stories, too, about other ancestors who anchored her to a continuum. As Madeleine’s biographer, I’ve read them all. Madeleine’s family tree flowered opulently, lush with lore and Americana, in all its triumphs and sins: Old World origin stories, one-way voyages across the Atlantic, a fateful shipwreck, colonialism, slavery, Revolutionary and Civil wars among smaller scuffles, westward pioneering, and American bootstraps prosperity. As Madeleine grew up, these texts filling the deep well from which she drew her identity and literary inspiration. In her Reconstruction-era novel

As Madeleine grew up, these texts filling the deep well from which she drew her identity and literary inspiration. In her Reconstruction-era novel

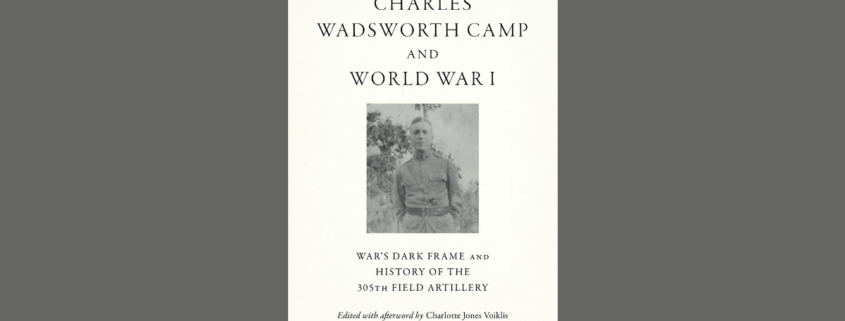

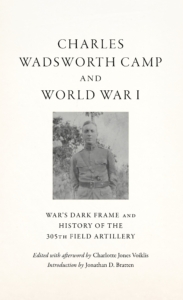

Charles was a journalist, critic, novelist, and playwright, and this new volume is a compilation of his two books on the war, one written as a journalist covering the conflict before the US entered it, and one written as a soldier. It features and introduction by historian and National Guard officer Jonathan D. Bratten and an afterword by Charlotte Jones Voiklis. Bratten’s introduction puts Charles’ journalism and history in context, and describes the formation of the National Army. Charlotte’s afterword is a personal reflection on family history and Charles’ influence on his daughter Madeleine.

Charles was a journalist, critic, novelist, and playwright, and this new volume is a compilation of his two books on the war, one written as a journalist covering the conflict before the US entered it, and one written as a soldier. It features and introduction by historian and National Guard officer Jonathan D. Bratten and an afterword by Charlotte Jones Voiklis. Bratten’s introduction puts Charles’ journalism and history in context, and describes the formation of the National Army. Charlotte’s afterword is a personal reflection on family history and Charles’ influence on his daughter Madeleine.

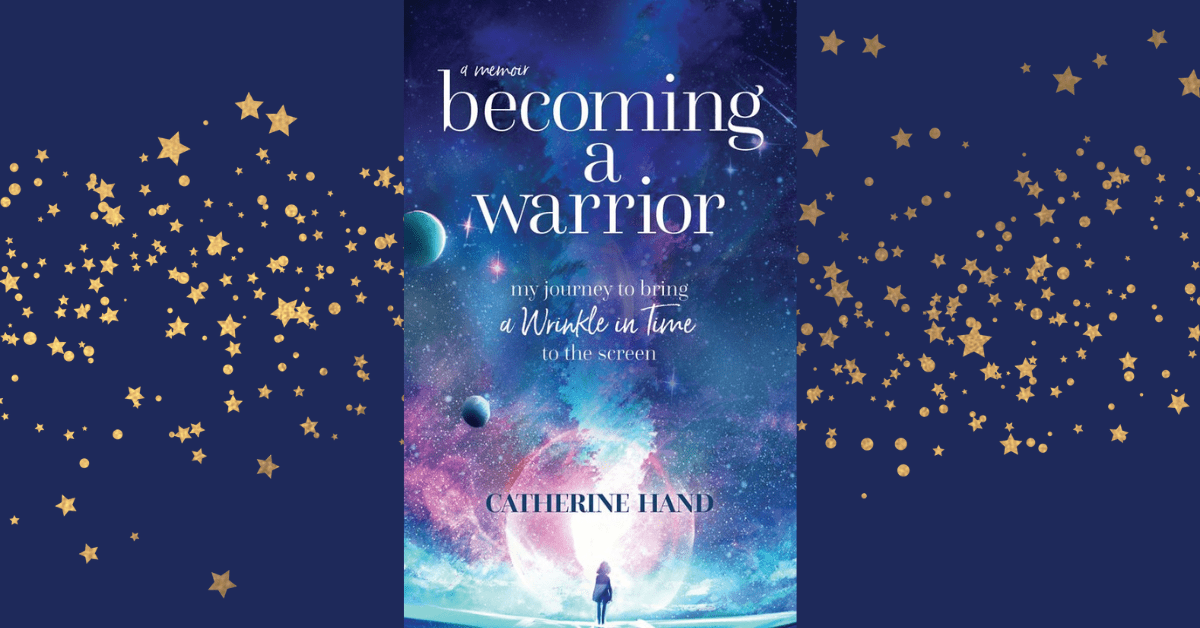

The first time I saw her in March 1979 she was standing near the elevator in the lobby of the North Tower at the World Trade Center in New York City. She was taller than I expected and wore flowing layers of colorful clothing

The first time I saw her in March 1979 she was standing near the elevator in the lobby of the North Tower at the World Trade Center in New York City. She was taller than I expected and wore flowing layers of colorful clothing