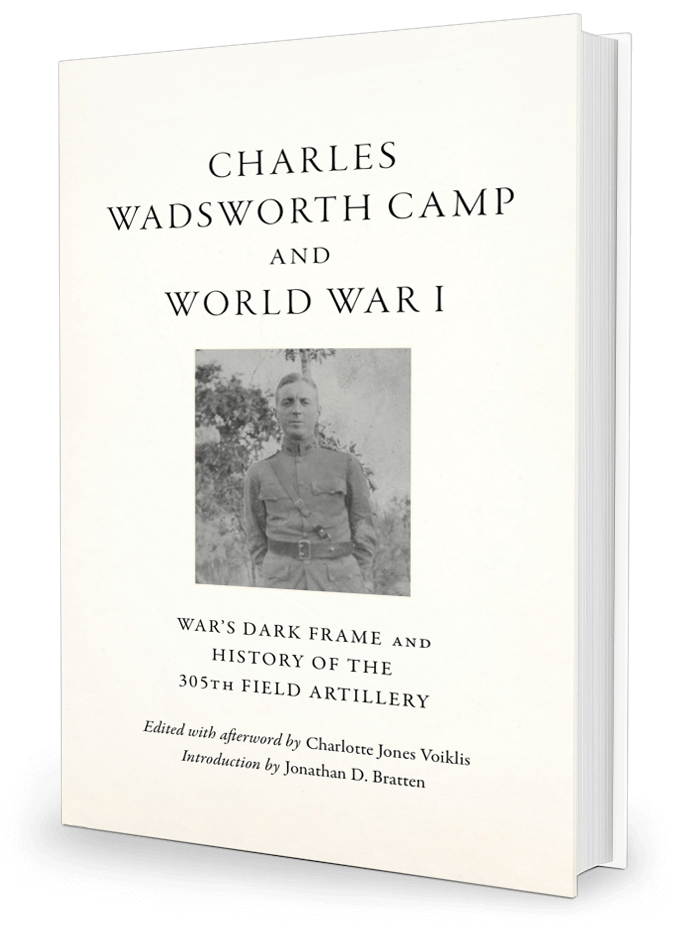

Charles Wadsworth Camp and World War I

Charles Wadsworth Camp (1879-1936) was a journalist, novelist, and critic who covered World War I as a reporter, and who also served in it as a soldier. He wrote two books about his experience, published in his lifetime and now in public domain. War’s Dark Frame was compiled from his journalistic dispatches, and History of the 305th Field Artillery is an account of his army battalion. Charles was also the father of the author Madeleine L’Engle (A Wrinkle in Time), who was born while he was deployed. Charles’s experience of the war left a profound mark on him, and also on his daughter.

The manuscript includes an introduction by Jonathan Bratten, the Maine National Guard Command Historian and the Army Center of Military History’s first Scholar in Residence at West Point. Bratten’s introduction puts the two books in their military and historical context. Charlotte Jones Voiklis, Charles’s great-granddaughter and Madeleine’s granddaughter, has written a personal essay that discusses her changing understanding of Charles’s biography and his profound influence on Madeleine.

War’s Dark Frame (1916) begins on the transatlantic journey from New York to England and continues to France. He was based in Paris and took trips to the British front. The books documents conditions, and also discusses espionage, conscientious objectors, and people’s amazement that the U.S. has not yet entered the war. It is both reportorial and witty, with a definite point of view, but it is not pro-war. As Bratten puts it,

“What Camp emphasizes, instead, is just how horrible the war itself is for people, rather than nations.”

History of the 305th Field Artillery (1919) is an account of the formation of the battalion, the time spent training, the progress made and skirmishes fought, and the long time it took to come home.

These two books, newly collected, revised and edited by his great- granddaughter, tell an interesting story about the U.S.’s reluctance to enter what was seen as a European conflict and the efforts to raise and train a draft army from its heterogeneous population. Often called the “lost generation,” veterans of World War One were largely silent about their experiences. The war and the 1918 flu pandemic largely did not make their way into popular culture and have been under-explored and exposed. Additionally, those who wish to understand Madeleine L’Engle will need to know her father – after all, A Wrinkle in Time is the journey of a girl to rescue her father and her realization that he isn’t going to make everything better.

A professional copyeditor went over the text. The revisions include modernizing spelling, punctuation, and syntax, and gentle edits for sense and flow. In certain cases, brackets have been used to indicate explanatory text. The manuscript includes a “Note on the Text” that provides more details, and the overall goal was to create a book that the modern reader can engage with easily.

The original of History of the 305th Field Artillery includes additional ancillary material as well as illustrations. PDFs of the original editions are made available free of charge below.

From Jonathan D. Bratten’s Introduction:

This was far from Charles Wadsworth Camp’s first time to Europe, as he had traveled extensively before the war to London and Paris, as well as to Cairo and Shanghai. He and his wife, also named Madeleine (referred to as Mado in this volume for clarity), had loved to travel together. As mentioned above, he had reported on the war in 1914, and then on the Easter Rising in 1916. But seeing wartime Europe for the first time came as something of a shock to him. As he stated, “The world was different and wrong.” In particular, he found England transformed entirely by the war; in reporting on it, he gives his first jab at American isolationism: “All Britain is heart and soul in the war. Even then it was hard to accept as real the brilliant, careless complacency of our own country.”

From Charlotte Jones Voiklis’ Afterword:

While her relationship to her southern roots was full of contradictions and ambivalence, she took pleasure in the stories she chose to tell (and that had been chosen for her, for there were many that had been passed down to her). She continued to tell those stories, not just to her grandchildren, but to her readers, too, keeping their memories alive but also fixed like a doll on a shelf that could be taken down and petted but not played with too roughly. I know there are other stories, too, that are not quite so pretty or proud, more like the shards of glass in the leather box—sharp and full of pain. Not all stories about her own parents and childhood were doll-like. Some of them were alive—shimmering, shifting, escaping her deft narrative skills—and created in me a curiosity and skepticism.